The inherent playfulness of who we really are—Naked Mind—is endlessly luminous, shining as the perpetual creative potential of our ceaseless spontaneity.

Inconceivably playfully, just for the fun of it, we’ve wired up The Matrix to wire us up to grow out of make-believe. We have, moreover, wired it up to wire us up to believe escapism is perfectly harmless as long as we keep hard wired in our head the fundamental operating principle that actual escape from this so-called ‘reality’ we inhabit is totally impossible, that thinking otherwise is literally psycho.

What we’re doing in fact is no different from me and my little nephew playing monsters. We’re wiring up The Matrix to wire us up to make it as hard as as we can possibly think of to escape, because then when we do escape it’s all the more fun.

Indeed, every good story’s got to have not only a really good villain, but a really good crisis—the point at which the story has to go one way or the other. The hero gets totally crushed, or she totally triumphs. In really, really good stories at the moment of crisis, the hero’s plight looks hopeless. Triumph is impossible.

Which is precisely where we find ourselves.

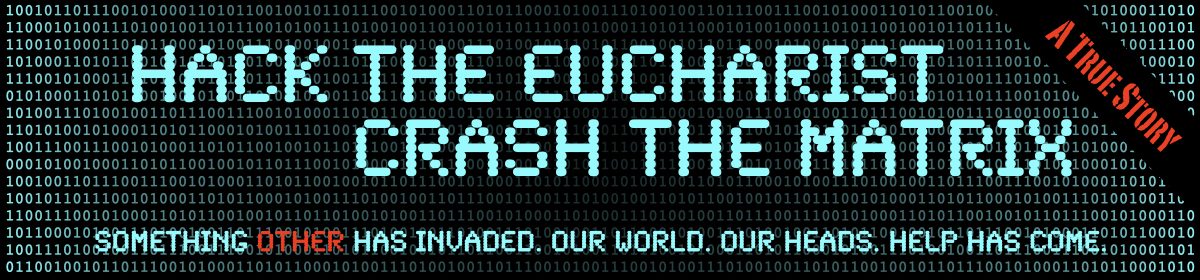

We can crash The Matrix, sure. But, Dick tells us, it’s gonna take a literal miracle. It’s gonna take a sacrament, for chrissake—a SAC-RA-MENT.

And if that’s not hard enough to swallow, on top of that, Waite tells us, not only does Dick not even have the right sacrament, worse, we don’t even know what the right sacrament is.

Holy shit.

But in really, really, really good stories the impossible happens. Because the hero realizes the impossible only looks impossible. And it looks impossible only because we—the hero, us—we’re looking at it all wrong because we got our head wired all wrong.

Then—bam!—the synapses untangle, the circuits rewire, the hero discovers the dazzling twist we—the hero, us—could never even dream of is staring us all right in the face.

Remember Interstellar? The “ghost” Murph thought haunted her bedroom when she was a kid turns out to be indeed real. The presence, the intelligence she sensed as a kid is her dad, Coop, messaging her from inside the tesseract, from outside spacetime using the stuttering secondhand on the watch he gave her to transmit, coded in Morse, the very information she needs to save all humankind.

Escape isn’t impossible.

Become as little kids, just like Jesus tells us, and a realm unimagined opens.

Every little kid without exception, just like Clarke tells us, lases into a being of pure consciousness in a fierce moment of inconceivable metamorphosis.

Because all appearances—the way things look, whether it’s the bread and wine, whether it’s the totally impossible—the Tibetan Buddhists tell us, are the inherent playfulness and inexhaustible potential of the ceaseless spontaneity of Naked Mind.

Recognize The Matrix—aka the bread and wine, aka the totally impossible—recognize all appearances as the form of your own mind. Recognition and liberation are simultaneous.

Recognize The Matrix—the bread and wine, the totally impossible—as coming forth from your own brain and shining vividly upon you, and in a soundless concussion of light, as Clarke says, it gives up its energies.

The Matrix—the bread and wine, the totally impossible—is no more. Just as Clarke tells us.

Instead all that’s left is all there ever was. Pure Consciousness. Naked Mind. At play.