I have reason to suspect,” says Whitley Strieber in The Super Natural, “that the form we live in every day of our lives is not our only state.”

Strieber and Kripal, The Super Natural, p. 97.

“I want to propose the idea,” his co-author Jeffrey Kripal adds, “that a rare but real form of the imagination may be what the conscious force of evolution looks like.”

Strieber and Kripal, The Super Natural, p. 118.

✋

Dang it.

That’s at least where I’d hoped to start today’s post.

I should’ve thought this through better.

We can’t talk about the super natural, about woo—about, you know,

a l i e n s—without first getting something out of the way.

Science is, let’s be honest, hopelessly dogmatic. Sure, it’s true scientists are (eventually) willing to change their minds if presented with a sufficient quantity of reproducible experimental data that falsifies what they hold to be true. But that method of establishing what’s true—reproducing experiments to gather sufficient data—is exactly what they’re dogmatic about.

Their unalterable and dogmatic belief is that

(a) because there exists a class of things that can be said to be true because the data from repeated reproducible experimentation has failed to falsify them, ergo

(b) only the class of things that can be subjected to repeated reproducible experimentation—only that class of things even can exist.

Science’s dogmatic belief system blinds it to the possibility that maybe, just maybe an experiment has failed to gather data that corroborates a phenomenon because maybe, just maybe the phenomenon is outside the scope of what the apparatus of a controlled reproducible experiment is able to detect.

No, no, a thousand times no!, Science protests. There is no other way to look at things, it proclaims dogmatically and infallibly, stomping its dainty little foot for good measure. There is no other approach. Period.

But the truth is, the fact is any way of looking quite naturally always fail to see what’s outside its scope. We can’t see x-rays with the unaided eye or a radio transmission with the unaided ear because that’s not the what our eyes and ears are designed to detect.

Likewise, if you look at sex purely with an eye to the mechanical design of the human body, it’s perfectly accurate to say men are designed to have sex with women, women are designed to have sex with men. But we know that some women prefer to have sex with other women, and they manage quite nicely, thank you very much; some men prefer to have sex with other men, and they have a delightful time of it by all accounts. Moreover, some people are quite certain that the original factory configuration of the body they were born with isn’t the one that fits them—who they are—best.

What the ‘the mechanical design of the body’ way of looking fails to see, trapped as it is in its focus on the apparatus of sexual reproduction, is another far richer realm beyond the mechanistic: it misses the whole wild human experience we have of what it’s like living life as a sexual being, what it’s like immersed in a consciousness that responds to and interacts with other earthlings sexually. Seriously, come on, no sci-fi writer could’ve ever imagined such a totally mad state of consciousness if it didn’t already exist.

In precisely that same way, there are vast realms that science’s mechanical way of looking fails to see.

There is of course absolutely nothing wrong with the way science looks at things. If it weren’t for the way science looks at things, there’d be no vaccine to boost our immune system to help us ward off COVID. What is wrong, however—and deeply wrong—is science’s dogmatic and petulant insistence that the way it looks at things is the only way to look at things—and its hopeless delusion that what it can’t see just isn’t there. Crikey.

To paraphrase Philip K. Dick only slightly, reality is that which, even when you don’t believe in it, doesn’t go away.

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

Dick, I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon, p. 4. .

Carl Sagan’s famous assertion that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof implies a question nobody ever seems to have the presence of mind to ask: extraordinary to whom? What may be out of the ordinary to Dr. Sagan may be perfect ordinary to Abbot Chö. Precisely what entitles Dr. Sagan to decide for the rest of us what is out of the ordinary?

Reality is that which, even when you can’t believe it, Dr. Sagan, doesn’t go away.

Okey-dokey, that off my chest, back to—

“I have reason to suspect,” says Whitley Strieber in The Super Natural, “that the form we live in every day of our lives is not our only state.” “I want to propose the idea,” his co-author Jeffrey Kripal adds, “that a rare but real form of the imagination may be what the conscious force of evolution looks like.” And I’d like to suggest that Kripal’s ‘rare but real form of the imagination’ isn’t all that rare, and that we encounter the ‘alien’ all the time—we just aren’t paying attention.

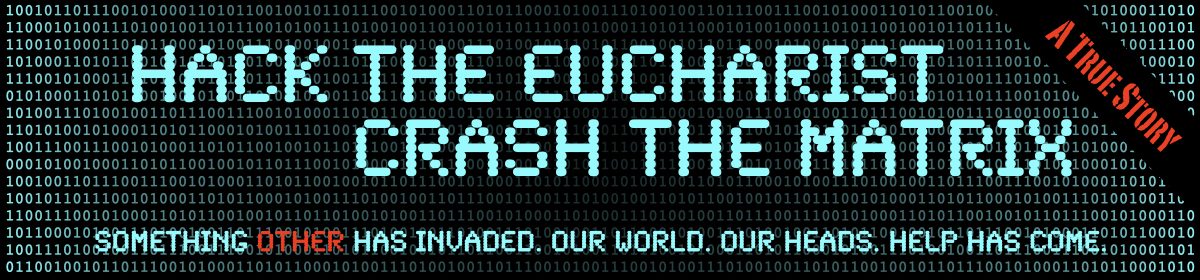

Coming 21 January 2022

You must be logged in to post a comment.