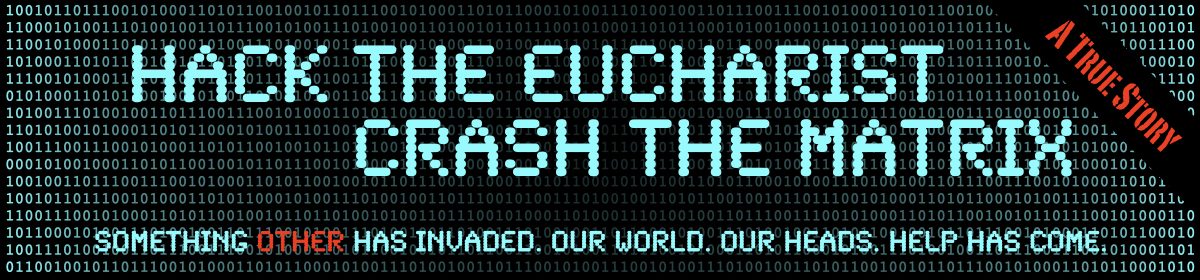

Come on, be honest, my whole premise is totally bughouse. Sure, I say, sure we can crash The Matrix. All we need is a sacrament, all it’s gonna take is a literal miracle.

Utterly absurd.

But Neo, remember—right after Morpheus tells him the truth, right after Morpheus shows him real reality—the very first thing Neo says is, “I don’t believe it. It’s not possible.”

Nope, indeed it’s not possible. The Hack’s absolutely not possible. In fact, it’s beyond not possible, it’s incomprehensibly absurd. Or it looks that way, and for a very good reason. That’s the way The Matrix has us wired. Or rather, as I said a couple of posts ago, that’s the way we’ve wired up The Matrix to wire us up: so that we’re hardwired to see only the impossibility of The Hack, the absurdity of the technology.

For now we see through a mirror darkly,

1 Corinthians 13:12.

as the Apostle Paul said.

What in fact we see darkly in that mirror is the reflection of our own playfulness, my little nephew and me playing monsters, Glorious Great Buddha-Heruka springing forth from our own brains to bar the way, his nine eyes wide open in terrifying gaze, his eyebrows quivering like lightning.

Or to put it another way,

We see through a UI darkly

—the UI being the way we’ve wired up The Matrix to wire us up.

Turns out, the only way to win the Great Glorious MMORPG is to hack the UI, to hack the whole damn game—just like Starfleet Cadet James T. Kirk after flunking Kobayashi Maru twice, the night before his third try, sneaks in and hacks the simulation, tweaks the algorithm so he could win what was intentionally programmed to be an impossible no-win scenario. For which Cadet James T. Kirk gets a special commendation for original thinking. And, implicitly, for unruly action.

So, indeed, glimpsed through the UI darkly, The Hack—a sacrament, for chrissake, a literal miracle—is impossible and absurd.

But this is one of those junctures at which we need Blind Kent, who isn’t blinded by the UI we see through darkly, to discern what’s really going on. In this case Blind Kent is, surprisingly, the second century Christian author Tertullian, who famously said,

Certum est quia impossibile est.

You can be sure it’s true precisely because it’s impossible.

Less famously, but maybe even more to the point, he said,

Prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est.

It’s absolutely credible precisely because it’s absurd.

The adjective ineptum would’ve set Blind Kent’s antennae all aquiver. Interleaved with the meaning absurd is another meaning: chartae ineptae is the phrase the Roman Poet Horace used for waste-paper, wadded up scraps like the Burger King wrapper in the gutter right next to Dick’s beer can, stuff that’s totally useless, like the seemingly malfunctioning second hand on Murph’s watch.

It’s absolutely credible, Tertullian is telling us, precisely because it’s trash, precisely because it’s totally useless—so keep your antennae tuned.

To be perfectly honest, Tertullian wasn’t of course talking about the impossibility, the absurdity of using a sacrament, a literal ‘miracle’ to crash The Matrix when he made either of those statements. Both quotes are from his treatise De Carne Christi (On the Flesh of Christ), in which he argues that God absurdly decided to incarnate his son in actual meat

to confound the wisdom of the world.

De Carne Christi, §4. New Advent (www.newadvent.org/fathers/0315.htm), retrieved 2 November 2021.

“The symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum,”* as Dick says, precisely “to confound the wisdom of the world.” No, I take that back. Über-Mind isn’t out to confound anybody on purpose. It’s just that, as Jacques Vallee observes, the actions of a superior intelligence always seem—must seem—absurd to an inferior one.† And when “the wisdom of the world” is, as in our culture, predominantly scientific (and notoriously impatient with woo), stuff that seems absurd gets wadded up pretty quickly—magically transformed as it were, presto!, change-o!, into Horace’s waste paper—and tossed.

*VALIS, p. 254.

†Dimensions: A Casebook of Alien Contact, p. 167.

Which is, of course, all part of Über-Mind’s dazzlingly cunning plot!, because the litter in the gutter, the trash in the dumpster—the stuff The Matrix has us hardwired to ignore—getting “the wise” to first process it (wad it) and then store it (toss it) into the trash stratum is precisely the way Über-Mind slips the really genius tech through the firewall and into The Matrix’s code without tripping any sensors.

Über-Mind in fact has a whole nother layer of sleight of mind at work to outwit The Matrix, which is this: what Tertullian thought he was talking about, his literal message, isn’t the real message. The real message is what’s interleaved in the harmonics of the literal message.

If some benign yet superior intelligence has invaded our world, invaded our heads, it’s pretty much got to be putting ideas in our little craniums we don’t ourselves even yet fully grasp. On one side of the coin, Jesus (as I’m growing more and more certain) never really meant for his disciples to grok the Eucharist. On the flip side, Tertullian wasn’t really saying what he thought he was saying. Or rather, he was saying exactly what he thought he was saying, but he was also saying something he had no idea he was saying.

And what he was saying that he had no idea he was saying was addressed to somebody else to grok the full import of. Namely us.

Why us? Because we’re the ones who listen when Jacques Vallee tells us that the actions of a superior intelligence must always seem absurd to an inferior one.

We’re the ones who listen when Dick tells us the symbols of the divine show up first in the gutter.

We’re the ones who watch Dave Bowman cross the event horizon into the monolith, we’re the ones who are inexorably drawn in with him not in spite of, but precisely because at that moment logic ceases to obtain.

The truth is, if The Hack—crashing The Matrix with a useless sacrament, a literal ‘miracle,’ some magic woo—were merely impossible, it wouldn’t be much of a challenge. Because a challenge that’s merely impossible won’t get us anywhere. Because the impossible may not be possible, but at least it’s understandable. And as long as we can wrap our hardwired little heads around it, The Matrix has us right where it wants us.

The real question is, if The Hack were—forget about impossible, we’d crack that like Miguel Alcubierre found a way to hack space with the Alcubierre drive* to do the impossible and travel faster than the speed of light—the real question is if The Hack were at least comprehensible, at least something we could wrap our head around, if it were at least nice and neat and logical, if it were not utterly and deeply absurd, totally alien—

He that eateth my flesh, and drinketh my blood, dwelleth in me, and I in him.

John 6:58.

—why haven’t we logicked or scienced or computered our way to it? Why the heck are we all still trapped? Worse, why are we still unaware that we’re trapped, why are we still like Neo when he thought he was Thomas Anderson, just another drone in another cube, until the Fed-Ex guy hands him the envelope with the cell phone at the other end of which he hears for the first time the voice of Morpheus.

*“Alcubierre drive,” Wikipedia (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alcubierre_drive), retrieved 24 December 2021.

Why? Because it’s a pretty sorry-ass leap, a pretty lame-ass metamorphosis that isn’t beyond all conceiving.

“So I hope you accept Reality as it is—absurd,”† as physicist Richard Feynman said. Because we’re not budging a femtometer outta The Matrix till we do.

Heck, maybe something totally bughouse like a sacrament is exactly what we need. I mean, for heaven’s sake, what did Morpheus give Neo? A red pill. Which Neo did take and eat.

†Okay, I’m paraphrasing just the eensiest little bit.

What Feynman actually said was, “So I hope you accept Nature as She is — absurd.”

QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, p. 10; quoted in “Richard Feynman,” Wikiquote (en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Richard_Feynman); retrieved 24 December 2021 Footnote.